Over the 2025 Thanksgiving weekend, 360 EEC Chief Technical Compliance Officer, Bryce Watson, was invited to a series of Kwakwaka’wakw Nation potlatches at the Fort Rupert Big House on Northern Vancouver Island.

Potlatches are sacred political ceremonies that mark major life transitions such as births, marriages, name-givings, memorials, or political declarations. These ceremonies were banned by the Canadian government from 1884 to 1951, and were allowed after major revisions to the Indian Act removed the ban. Potlatches are held in a Big House, where sand surrounds a central fire pit, and seating lines the perimeter. Guest chiefs sit at the front of the sand area, with performances taking place before them. Singers and drummers sit directly behind the chiefs, sharing ancestral stories through songs, dances, and oral storytelling. The host family sits to the right of the chief, while the rest of the community fills the remaining space.

Potlatch History and Protocol

Chiefs rarely speak during the event; instead, they appoint a speaker to represent them and maintain order in the Big House. Disrespectful behavior is strictly prohibited, and fines are issued if protocol is not followed. This includes moving during a performance, running on the dance floor, or disrupting a dance. During one performance, some children ran through the Big House. At the end of the dance, their father addressed the audience, acknowledging the disrespect and the breach of protocol. He presented the chief with a cheque for $1,900 and stated, “Our children have learned a valuable lesson, we will never speak of this again.”

Each potlatch begins with a series of local welcome dances, followed by a customized program designed by the chief to “take care of business.” This business often addresses personal or community matters such as environmental concerns, unity, gratitude, or shared learnings. Every dance or story performed is a legend owned by the hosting family or performed with permission from the rightful owner. After the performances, each chief shares what the potlatch meant to them, expresses gratitude, and exchanges gifts. The event concludes with the hosting chief presenting a witness gift to everyone in attendance—ranging from masks and native coppers to apples.

Kwakwaka’wakw Nation First Potlatch

The first potlatch I attended was hosted by an elder chief to honor and name his newborn granddaughter and celebrate his 50th wedding anniversary. It was a mature, intimate gathering attended by 18 chiefs from coastal nations. A significant moment during this potlatch was the repatriation of a totem pole used in the Wild Man dance, returned from the United States.

Chief Calvin Hunt wrote a song and performed a dance about kissing his wife in the moonlight after much rejection—celebrating their 50 years of marriage. The potlatch concluded with a group dance about crossing the mountains on the Grease or Eulachon Trail. Eulachon are small, high-fat fish traditionally harvested by the nation and traded across coastal British Columbia and the southwestern United States.

I received an apple at this potlatch, and sat with Janet Child, the band manager and wife of Tom Child, 360 EEC’s Indigenous liaison.

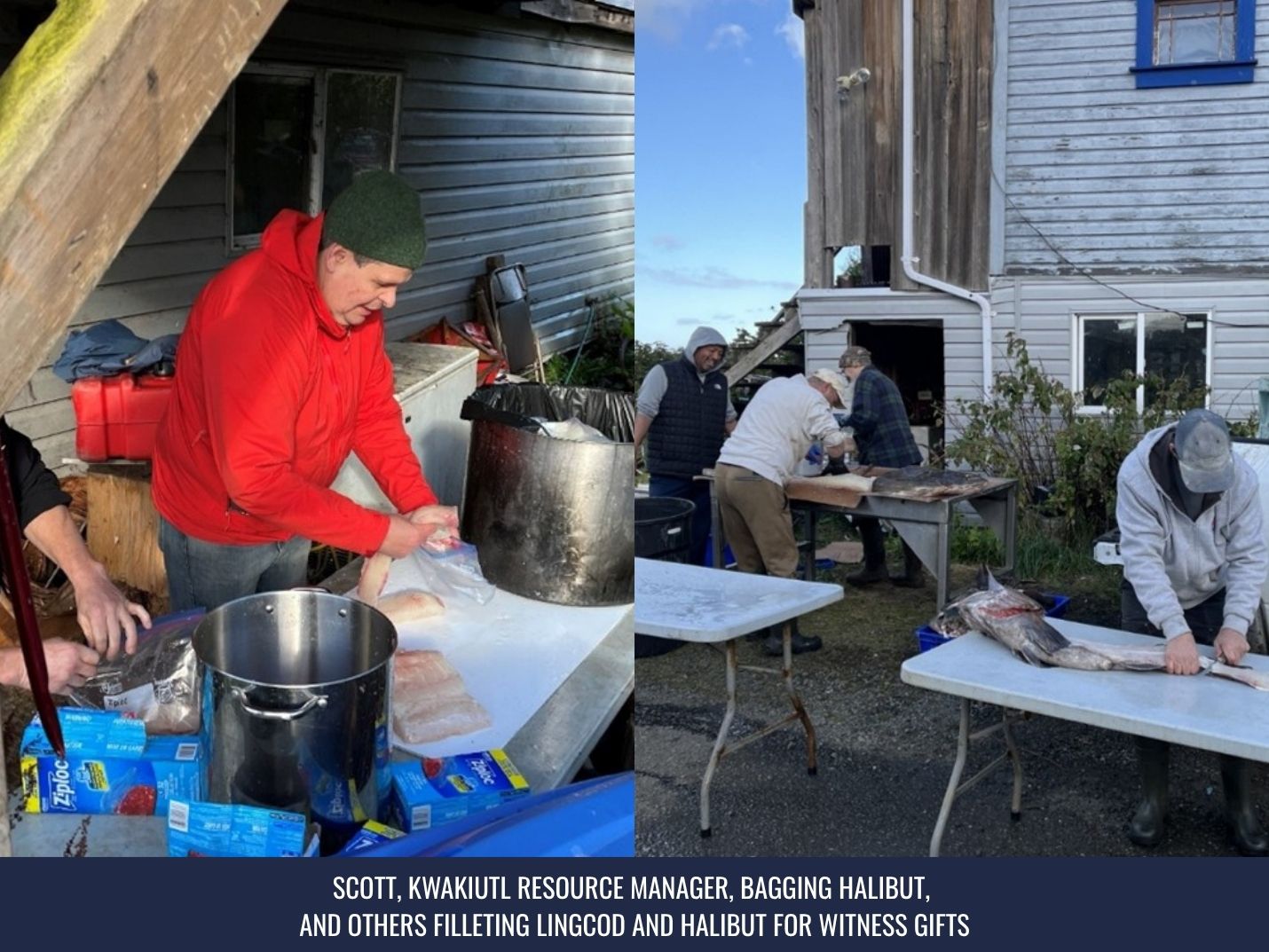

After the potlatch, I visited Chief David Knox’s home on the reserve. I offered to help and was quickly put to work filleting and bagging fish for witness gifts for the second potlatch. While there, I met Scott, the Kwakiutl resource manager, at the halibut bagging table, and Alex, a mental health expert working with Chief Knox on a youth project.

Kwakwaka’wakw Nation Second Potlatch

The second potlatch started at 9 am, and focused on conservation and community collaboration. Twenty-six chiefs were present, from Haida Gwaii to the Salish Sea (Victoria). On my way to the Big House, I noticed a few people working on something and offered to help.

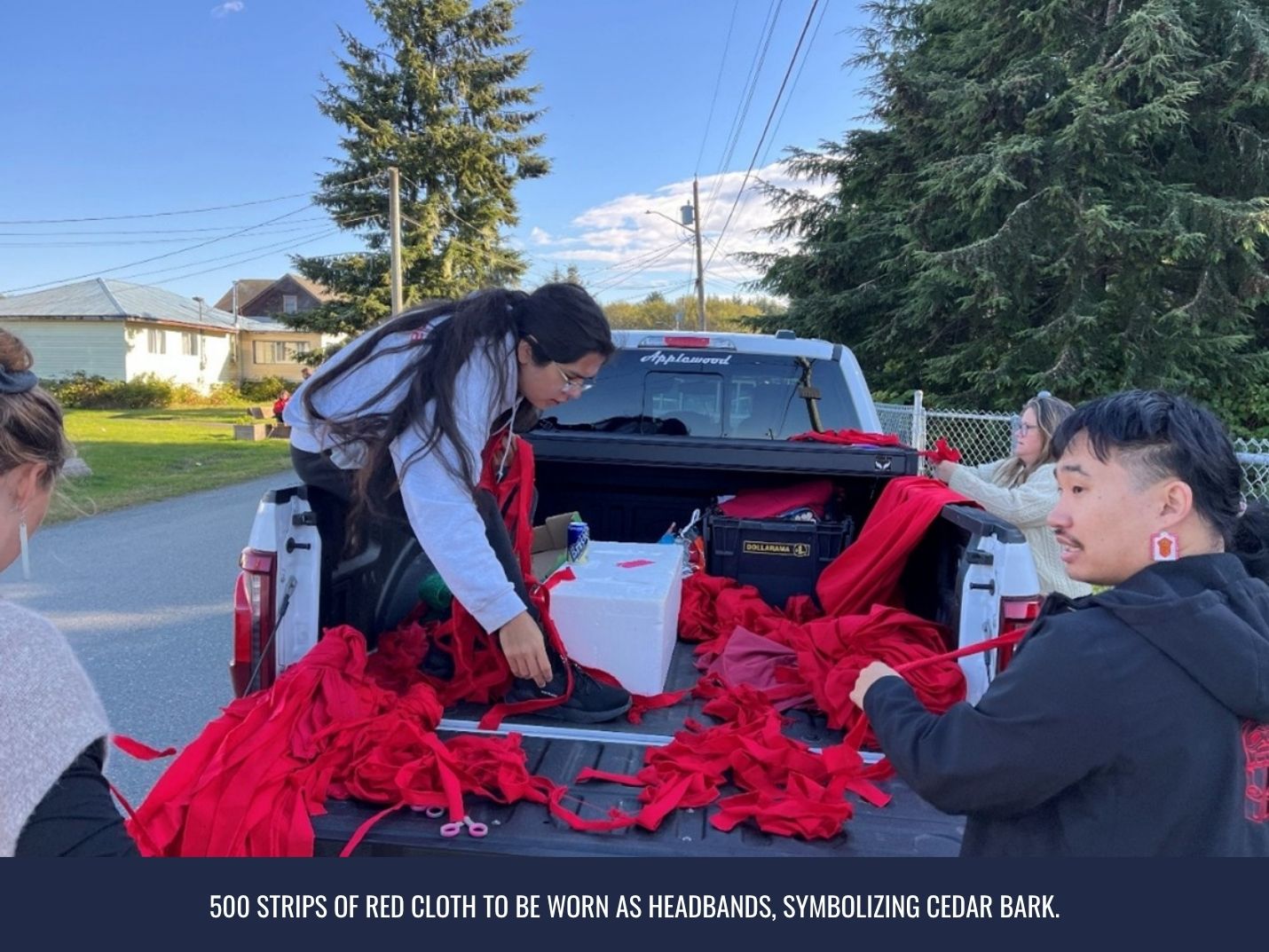

I spent the next hour tearing 500 strips of red cloth to be worn as headbands, symbolizing cedar bark. Everyone at the potlatch wore either cedar or cloth strips, which were later collected and burned to protect the village.

There is a legend that an elder once had a vision of a threat, and the community used the protective qualities of cedar to save the village by wearing and then burning the bark. To symbolize this, everyone returns their headband during the event to be burned. Those experiencing adversity are asked to keep theirs; otherwise, the headbands are destroyed collectively for the community’s protection.

While delivering the headbands, a man with wild hair asked for 40 of them for a dance. He turned out to be Mervin Hunt, a renowned carver. I spent the next hour making hemlock sashes with him—a pillar of the community.

We talked about my family, his health, and my outfit. It turned out the blanket I was wearing was intended for a woman. He took it from me and wore it himself, a gesture of respect to help me save face.

After finishing the sashes, I met up with my friend Tom, who suggested a walk on the beach before the next dance. We walked about 300 meters along the historic village site by the ocean, and he shared its history. We discussed the fish traps on the beach, petroglyphs, the village layout, and the decline of fish populations. I was fortunate to find an extremely rare blue trade bead.

The first sacred dance after the welcome dances was the Hamsamala, featuring the four servants of the Man-Eater of the North World—Baxbaxwalanuksiwe’. These four birds fetch food for Baxbaxwalanuksiwe’ in the form of humans. At the end of the dance, the Man-Eater is driven away. In this powerful dance, a father or warrior dances with a child and escapes.

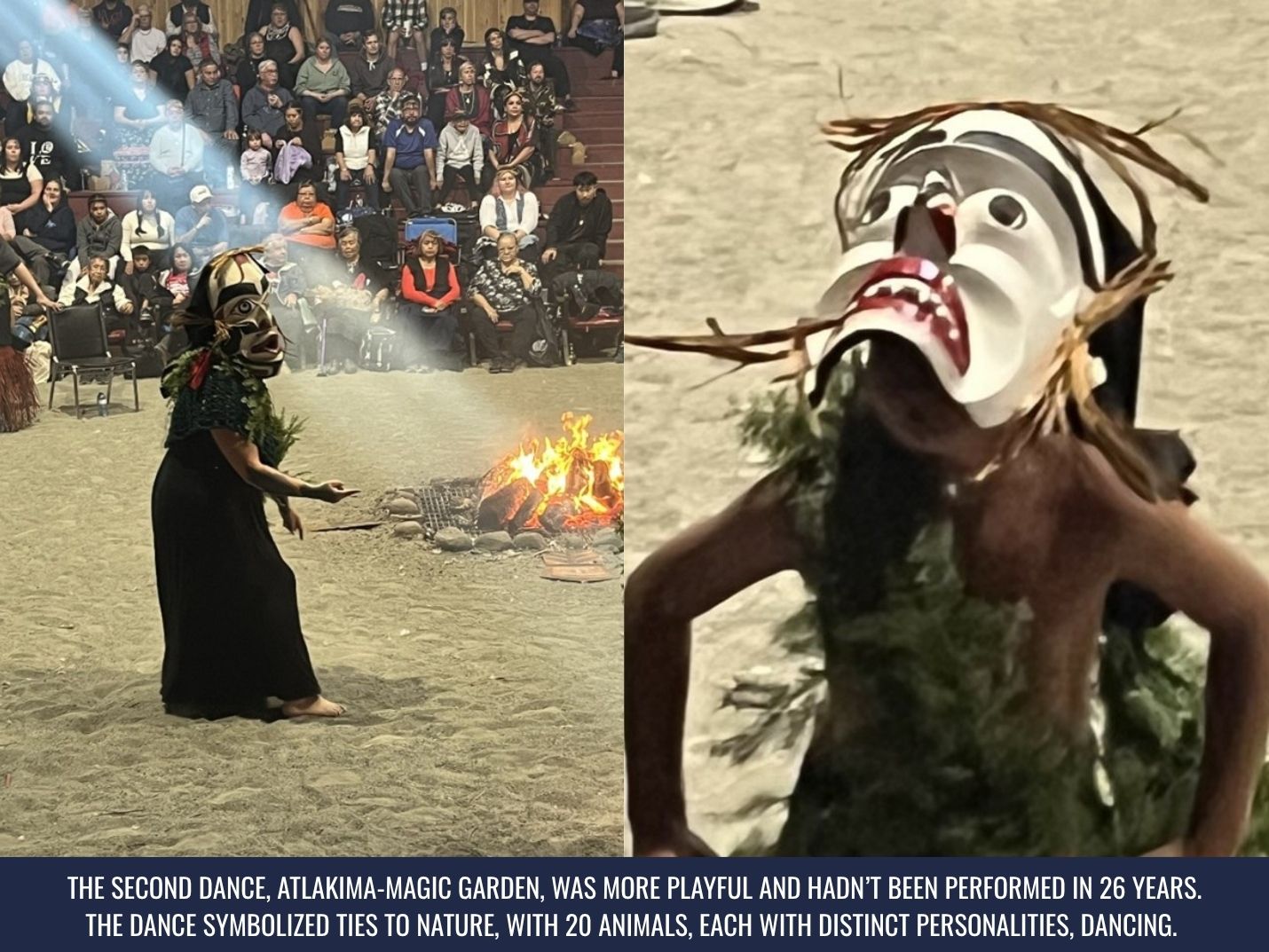

The second dance, Atlakima-magic garden, was more playful and hadn’t been performed in 26 years. The song and dance were passed down from relatives in Rivers Inlet and featured forest animals and people—grouse, deer, salmon, etc. This is the dance that used the sashes that I helped to make earlier.

The Magic Garden dance symbolized ties to nature, with 20 animals, each with distinct personalities, dancing. A young girl was “born” from beneath another dancer’s costume, representing renewal and life.

The potlatch wrapped up after 12 hours with a speech from Chief Knox addressing environmental concerns and the cumulative impacts of industry. The community is deeply committed to working together to ensure resources are preserved for future generations.

360 EEC: Service Rooted in Reciprocity

We believe meaningful service happens when listening and learning are paired with action. Our consulting approach is built on reciprocity: Sharing expertise while honouring the knowledge, values, and priorities of our partners.

360 EEC now has the opportunity to work directly with the Kwakwaka’wakw Nation and will begin initiating grants and proposals in partnership. On November 1, 2025 360 EEC has been invited to another potlatch in Port Alberni with a restoration theme. This will further solidify our role as a trusted partner and advocate within the community.

Thanks for reading,

Bryce Watson

About the Author

Bryce Watson P.Geo., Chief Technical Compliance Officer

Bryce is a registered Professional Geoscientist in British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Ontario and is a founding partner at 360. As Chief Technical Compliance Officer, he is regarded as a leader in the environmental space and acts as an executive advisor internally and externally to multiple clients; providing strategic closure and regulatory planning to align execution practices with corporate strategy.

With over 25 years of experience in the environmental and regulatory fields, Bryce finds innovative and economic solutions to address environmental and regulatory issues while still operating within the existing regulatory framework.